The launch of Wal-Mart’s sustainable product index has generated much comment, some positive and some not so complimentary. Ben Cooper examines the response from environmental commentators and campaigners.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The phrase ‘damned if they do and damned if they don’t’ might have been coined to describe how corporate giants must feel when launching responsible business initiatives.

When Wal-Mart unveiled its sustainable product index last month, the company would have been expecting a sceptical response from some campaigners and was not disappointed. Whatever it may achieve in the long term, the move does not appear to have compromised Wal-Mart’s membership of the corporate pariah club.

The index aims to establish a “single source of data for evaluating the sustainability of products”, says the retailer. Wal-Mart will begin by sending a 15-question survey to its 100,000-plus suppliers, covering energy and climate; material efficiency; natural resources; and people and community.

The second stage will be to create a consortium of universities that will collaborate with suppliers, retailers, NGOs and government to develop a global database of information on the lifecycle of products from raw material to disposal. The final step will be to translate the information into a consumer-facing sustainability rating for products.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataActivists have been quick to suggest that the scheme lacks credibility; that the questions are too vague; that some sustainability components, such as hazardous chemical usage and recyclability, have not been addressed.

Critics have also argued that, in spite of being described as a ‘product’ index, the scheme is not as yet rating individual products; and that, while the index can potentially allow companies to be compared with one another, no benchmarks are being set.

Above all, there is a prevailing tone in the criticism that it is presumptuous and hypocritical of a company with a moderate record on environmental achievements – and an even worse one on social issues – to put itself in the position of ethical arbiter.

There will always be a segment of the campaign community that will be extremely hard to convince. Others, however, take the view that this is a step in the right direction, and if Wal-Mart is using its massive leverage for the environmental cause, rather than simply to eke out a few more cents in margin that is something to be welcomed.

Kurt Davies, research director at Greenpeace USA, says the retailer deserves some credit for taking this step. “A lot of people are very sceptical of it, and sceptical of anything they do and I think that’s with due cause,” Davies tells just-food. “But looking at the questions they’re asking, the majority of the companies that supply them have never been asked these questions before.”

He believes Wal-Mart’s capacity to influence its suppliers makes this a significant event. If a supplier has to answer ‘no’ on a Wal-Mart questionnaire, it will “want to answer yes next year”, Davies says. He adds: “If we sent this survey out to companies, we’d probably get a 10% response rate. These are big questions that a lot of activists have been working to make law for many years.”

Environmental commentator Joel Makower also believes Wal-Mart’s power and influence will be a force for change. “It’s definitely a bold move, one that stands to raise the bar on sustainability and transparency, empowering both retailers and consumers to leverage their buying power to affect change,” Makower writes. “It stands to spur innovation in products and processes. And it appears to be around for the long haul. Wal-Mart has gone well beyond talking the talk here. It’s changing the game.”

|

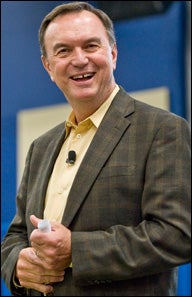

Wal-Mart chief Mike Duke outlines plans for the retail giant’s index |

Makower says Wal-Mart should be given credit for reaching out to universities, environmental groups, organisations like Business for Social Responsibility, its suppliers and consultants in developing the initiative. Among those whose opinions were sought was Yvon Chouinard, ground-breaking founder of eco-friendly fashion label Patagonia.

The multi-stakeholder engagement should continue, and hopefully expand, as it moves into its second stage and the development of the Sustainability Index Consortium, which may help allay concerns over credibility.

This point was also picked up by Ayesha Barenblat, director of advisory services at Business for Social Responsibility. Barenblat was a panellist at the Sustainability Milestone Meeting at which the scheme was unveiled.

Following the launch, she wrote in her blog: “During the meeting Wal-Mart’s senior vice president of sustainability, Matt Kistler, reiterated that this is not a Wal-Mart or even a US-led effort. The desire is for this to be a global effort used by retailers and suppliers in all countries around the world.”

The idea that Wal-Mart is not jealously guarding ownership of the scheme and would genuinely like to see it become a multi-stakeholder initiative plays very well with many commentators. In the Business Respect newsletter, UK-based corporate responsibility strategist Mallen Baker writes: “That’s when you know a company is serious about change. When they don’t need to own the thing, but recognise the thing will work better if it is independent.”

However, the notion that multi-stakeholder credibility can be added to an existing project at a later stage will not sit well with some activists, who will also point out that this is an intention rather than a reality. But the fact that the second stage specifically involves continued stakeholder dialogue underlines that this is a process, the initial phase of which can only be judged as precisely that, a first step.

What the more positive remarks tend to have in common is that they all acknowledge the potential for this initiative to be a catalyst for further change. Sceptical campaigners might also bear in mind that the majority of Wal-Mart’s customers are not exactly baying for this.

Yes, consumers are far more motivated by sustainability concerns than they were a few years ago but, in the mainstream US market that Wal-Mart all but owns, they can hardly be considered decisive motivations for most, particularly in the current climate.

But retailers lead trends too. And as a force for changing consumer attitudes and buying behaviour, the higher profile for sustainability that the scheme heralds and the impact it is likely to have in the supply chain could, ironically, vastly outweigh the campaigning efforts of many of those who have all but dismissed it.