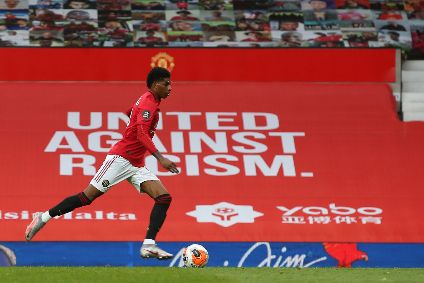

It was no surprise earlier this week to see major players from the UK food sector join a campaign, led by Manchester United and England football star Marcus Rashford, advocating three policy initiatives aimed at reducing child food poverty.

Six national retailers, Aldi, The Co-op, Iceland, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Waitrose, along with online delivery specialist Deliveroo, cereals-to-snack foods manufacturer Kellogg and, confirmed today (4 September), Kraft Heinz, have joined food charities FairShare and the Food Foundation in a child food poverty task force, calling for funding to be earmarked for the measures in UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s forthcoming Budget and Spending Review.

Rashford is rapidly becoming a captivating presence and potent voice in the food policy arena. Following his successful bid in June to reverse a UK government decision on holiday school meal vouchers, the media attention the task force has garnered this week has once again shown his capacity to cut through the political debate.

In many ways, it is hard to see much down side for the food firms backing the campaign. In fact, it almost seemed a little surprising only one food manufacturer decided to sign up. The food industry is often in the firing line on children’s food issues but this is a rare opportunity for companies to make common cause with campaigners. Meanwhile, being able to proclaim they are on the same team as Rashford, particularly as the footballer is adding human rights campaigner and consumer champion to his job description, is probably an even more tempting proposition, or at the very least companies want to avoid any association with what may stand in his way.

Indeed, just as in his day job, Rashford is someone both sides would rather have in their dressing-room than see emerging from their opponent’s. His palpably earnest commitment to the issue, borne out of his own childhood experience, coupled with his status, make him the kind of advocate politicians hate to find themselves up against, but the early signs are Rashford has a little bit extra. The articulate way he speaks about the issue, direct but gracious yet powerfully persuasive, not only flies in the face of some well-established, unflattering perceptions of top-flight footballers, but also shows the power of authenticity.

The UK government decided not to set itself against the Rashford bandwagon in June, and will be reluctant to do so now. Even without the Rashford factor, campaigners would have been optimistic for some concessions.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe launch of the UK government’s obesity strategy in July showed greater preparedness to engage more proactively on food policy than had at one stage been envisaged. Furthermore, the policy initiatives being called for, namely the expansion of free school meals to every child from a family on Universal Credit or an equivalent state benefit, the extension of holiday provision (including food and activities) to all children on free school meals and increasing the value of the Healthy Start vouchers from GBP3.10 to GBP4.25 (US$4.09 to $5.61) per week and extending these to all on Universal Credit or equivalent, are all recommendations put forward in the Government-commissioned National Food Strategy report, published in July.

So, the companies concerned probably believe they are backing a winning ticket, while scoring plenty of points with consumers regardless of the outcome.

That said, food policy is a delicate area for food manufacturers. The common ground and shared convictions this campaign speaks to are to be welcomed but, how ever successful the Rashford task force may be, the food industry will remain in the cross-hairs of food campaigners on all manner of other issues.

While affordable access to sufficient food for children from deprived households is something any company adhering to basic principles of social justice could sign up to, there would be far less scope for consensus were the debate to gravitate towards affordable access to optimal nutrition for growing children. In fact, the debate is fairly likely to move in that direction, probably sooner than later, which may explain why only two food manufacturers have engaged.

Lower food prices are often hailed as a win for consumers, with food retailers and manufacturers acclaiming their ability to give hard-working families value for money. While average expenditure on food as a proportion of disposable income has fallen steadily in the UK over the years, with the proportion of outgoings spent on food consumed in the home now standing at 8%, by this measure the poorer the household, the more it effectively spends on food. Welfare measures to correct this, such as those being advocated by the task force, should arguably not be a matter of debate.

When it comes to ensuring affordable access to a balanced and nutritious diet, the picture is far worse. According to data from the Food Foundation, in order to follow a diet consistent with the Eatwell guide published by soon-to-be-defunct health agency Public Health England, the poorest 50% of households would have to spend nearly 30% of their disposable income on food. Families in the lowest decile would see almost three-quarters of their outgoings spent on food.

The implementation of the three policies being advocated by Rashford’s task force is simply a question of influencing government priorities, with its corporate backers well-distanced from any fallout. On the issue of the pricing and availability of healthier food choices, however, food companies are seriously exposed.

It will not have gone unnoticed among pressure groups that one of the food manufacturers to join the task force is a producer of breakfast cereals, one of the most issue-laden areas of the food market in relation to child nutrition.

The positive response on social media from Kellogg’s employees and other stakeholders underlines the potential for such engagement to motivate staff and make them feel good about their company, and enhance corporate reputation. That a little of Rashford’s stardust may be sprinkled on bowls of Corn Flakes or, more controversially, Coco Pops, is a tempting prospect but any company thought to be using the Rashford factor as greenwash will be harshly judged.

When discussion next turns to the issue of the nutritional profile of some breakfast foods targeted at children, Kellogg’s may well be reminded of its vocal support for the Rashford task force, not least by its two non-industry members.

That is not to say supporting such initiatives is unwise or unethical. Far from it. It is simply that companies have to live up to the spirit and principles such campaigns embody as both current and future actions will be judged in that context.

Food companies globally are at the epicentre of many critical food justice debates. Indiscriminate virtue-signalling is not only cynical in view of the industry’s responsibilities and, sadly, its culpabilities, but will almost certainly backfire.