UK supermarkets are heavily investing in the growth of cheap, intensively-reared industrial meat at the expense of animal welfare, public health and their own environmental commitments.

Advertising spend continues to be anchored around meat and dairy, for example, while conversations connected to the carbon footprint of meat and dairy are being “purposefully misinterpreted”.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Potential reductions in emissions from livestock, through, for example regenerative agriculture and carbon sequestration, are communicated as certainties rather than with caution and common sense.

Any debate on the consumption of livestock products is framed publicly as an attack on small farmers, yet these are the very ones being squeezed out of sustainable production systems (and the industry) because bigger is better when the market demands ‘more meat’ at the lowest possible price.

These are not the headline findings of the latest research from an environmental NGO, or a whitepaper from a left-leaning think tank, or even an academic paper assessing the power (im)balance in grocery supply chains.

No, these are the (alleged) realities of food retail from a group of industry professionals in what they call their ‘insiders guide to meat and dairy’.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThis topic is “the most perfect example” of why supermarkets and their supply chains are stuck on sustainability, one of the ‘insiders’ tells me. “We must find a way to have a conversation about this […] because we can’t afford to wait for the Government.”

Eating fewer burgers or drinking fewer high protein shakes to help tackle climate change is a hot potato that politicians dare not touch – and not least, as the insiders suggest, because of their close connections to large agribusinesses who continue to lobby for the ‘security’ of the status quo. This is, as the insiders say and the science shows, short-sighted; the focus for all parts of the business must be aligned on less and better, not more and cheaper meat and milk.

“[The current trajectory] will lead us to poorer environmental outcomes, poorer health outcomes, increased inequalities and more pressure on farmer livelihoods in the UK,” the memo reads. “It also creates material, financial risk for our industry and thus national food security. This is happening against a backdrop of a cost-of-living crisis, climate change and environmental degradation that means our operating environment will only get harder if we do not act now.”

Those in the insider group are not just chief sustainability officers and the like; they are also from other parts of food businesses who see first hand the clash between climate rhetoric and commercial reality.

People in this industry are not trying to do a bad job, explains Kate Cawley, founder of the Future Food Movement, a UK network of food-system experts and leaders “turning sustainability ambition into action” but they are stuck in a system that is broken and will bring huge business risks going forward. “I used to think you could disrupt this and reset,” Cawley, who is not involved in the insider group, explains, underlining we do need to be turning some of these “super tankers” around.

The insiders have similar ambitions but have realised they cannot do this alone. These are people who enjoy the work they do, respect the companies they work for and have close relationships with their colleagues. However, deep down they understand that what is happening day to day is not enough. “People assume we are a group that is all B Corp, sustainability professionals or young people … but we are not that,” explains one of the coordinators. These are people from big companies, in senior positions and from a range of functions. “We are also not asking them to change their companies from the inside,” the coordinator adds. “There is no five-point plan here.”

Protein push

This is the second memo from the group. The first, published in April last year, claimed investors were being given “false confidence” about the state of the food system.

The warning received considerable attention and was reinforced a month later after charity Feedback Global, supported by The Food Foundation, analysed UK food environmental ambitions. According to the report, the UK’s ten leading supermarkets had set 600 commitments relating to climate and emissions, land use and deforestation and sustainable and healthy diets between 2014 and 2024, but progress on these was lagging, with vague reporting and a failure generally to set much-needed, volume-based (sales) targets to tip protein portfolios away from livestock products.

The foundation’s State of the Nation’s Food Industry report also showed promotions and multi-buy deals to be weighted towards animal products – including processed meats – rather than plants. This is designed to drive footfall, with deals for cheaper meats partly subsidised by customers buying higher welfare, organic and regenerative products. “Very few people are making money from selling meat, yet it’s a strong perception driver of value and quality in the minds of the public,” another insider who is currently in post explains. “It is the devil you know,” they add.

This is, however, not a battle between good and evil – much as some might like to pitch it. While supermarkets and the big protein producers are cast as villains by campaign groups, industry has fought back through its representatives to hammer home the message that any attack on meat production is an attack on all farmers. The winner? The status quo. The loser? Society.

What we have is disparate and disorganised action and it is just not enough, says an insider. “We all need to act in concert,” they say. This is, as those involved highlight, about “collected, accepted self-deulsion”.

It’s really important that this memo has come out

Nusa Urbancic, Changing Markets Foundation

The memo is music to the ears of those who have been chasing these companies down for years, pushing not for a world full of vegans but the production of sustainable, healthy food that is available, affordable and offers farmers a fair price and financial security. “It’s really important that this memo has come out,” explains Nusa Urbancic, CEO at Changing Markets Foundation. “It confirms a lot of the things we have been saying for years … with polarisation delaying discussions about real transformation of our food systems.”

Changing Markets Foundation has reported how pilots focused on better meat and dairy are “inflated” in marketing strategies and ESG reports, which helps hide the misalignment between company net-zero plans and their commercial growth strategies. Plant-based proteins as well as regenerative options, Urbancic explains, are not seen as replacements for intensively-produced livestock products but additional growth opportunities.

Whether there are employees from such businesses within the insider group is moot but the answer lies only with the organisers who conduct all their calls in a low-tech, often 1-2-1 environment to retain the anonymity of the whistleblowers involved. The meat and dairy guide went through numerous drafts before being agreed, for example, with some admitting it was not as “pointy” as they would have liked.

The group is treading a fine line as it attempts to deliver hard-hitting, honest and hopeful messages. There have been claims – made vocally in opinion pieces in The Grocer – that the group is a bunch of activists “masquerading” as concerned insiders. This seems to have taken those involved by surprise – they could not have been expected to call out their companies without the protection of anonymity.

The format has also given others in Europe the confidence to come together. A group in France will have its first meeting this month, Just Food understands, and there is interest from food industry executives in Germany and Denmark. “We are thinking about the US, too,” says one coordinator.

Organisers hope their funding – none of which comes from corporates – can keep pace with the momentum. The rate of recruitment in France has been “four times faster” than in the UK. In any case, the interest is testament perhaps to the escalating climate crisis, combined with a year of supply issues, troubling harvests and rising prices, and geopolitical chaos. All this, as the first UK memo explained, “will have a meaningful commercial impact on our businesses, and yet we feel that there are a number of structural and cultural issues that are preventing the severity of this challenge being fully accepted by industry or fully shared with our investors”.

The group has set out 22 questions it wants investors to ask of food companies – from the amount of meat and dairy that comes from low-impact, high-welfare sources and the way in which bonuses are structured to incentivise meat sales, to the governance of climate commitments and the investment in product innovation to replace meat content in meals “without impacting customer experience”.

They also challenge the narrative around consumer choice – which is “being used as a defence against any industry agency over what is sold when, in reality, industry is impacting choice through product development, ad spend, pricing and discounting strategies. These strategies serve both to push sales of cheap and processed industrially produced meat, and to place a premium on alternatives”.

Meat motivations

Whether food companies back or believe in alternatives to cheap, intensive meat and dairy products is the elephant in the room here. The struggles of plant-based options in some markets have been widely reported. The challenges they face this year will surely intensify as the narrative around meat and dairy as ‘natural’ proteins takes hold (and already has in the US).

“Boards need to take accountability for a strategy [the growth of meat and dairy at all costs] that culminates in a major risk to food security,” explains Ned Younger, a director at Inside Track, who coordinated the guide. Investors must start asking tough questions of senior executives, adds another of the organisers, speaking on condition of anonymity. This is, they note, an “endemic failure of governance” as companies continue to offer a positive net-zero narrative in public but privately pursue profits at all costs.

Scope 3 emissions, which make up more than 90% of total emissions for food retailers, are a particular problem; and within those supply chain emissions it is meat and dairy that make up the lion’s share. Methane, considered as a climate change ‘brake’ given its short-lived nature and powerful warming effect, has become the focus for NGOs like Mighty Earth. Many companies are simply ignoring what is in front of them, suggests Gemma Hoskins, the organisation’s UK director.

Technical solutions as well as transition to lower input, regenerative agricultural practices will help reduce emissions, but not to the extent that environmental commitments, including those aligned with the Science-Based Targets initiative, can be met. Hoskins also highlights the “worrying” reports coming from Denmark in relation to the health of cows fed methane-suppressants (which are being investigated).

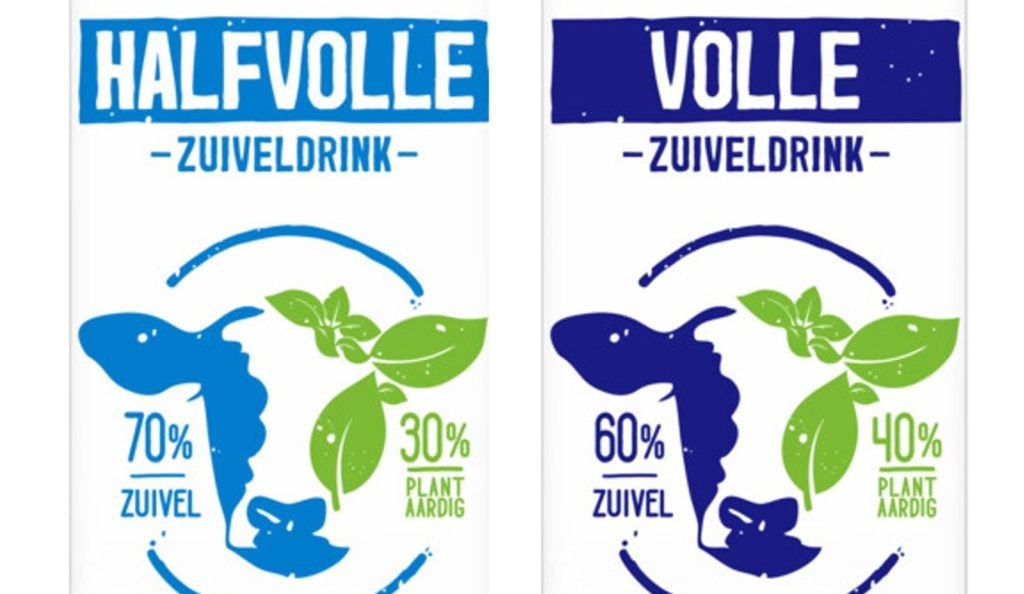

Some retailers have begun to accept the reality of the much-needed protein transition – and their role in driving change rather than relying on consumers. Consider Albert Heijn, the Dutch supermarket that has invested in hybrid dairy products under its private label and put them in direct competition with standard dairy options. This is about true protein transition leadership, explains Jakob Skovgaard, co-founder and CEO of PlanetDairy, which makes the ‘milks’ for the supermarket. “The Dutch government and Albert Heijn are actively driving the shift toward 60% plant-based protein by 2030,” he adds.

In Germany, meanwhile, Lidl continues to publish the ratio of animal and plant-based proteins in its sales: 11.8% and 6.6% of meat and dairy proteins respectively were plant-based in 2023; the 2030 target is 20% by 2030. Improved affordability is driving this change: according to a 2024 study published by the ProVeg nutritional organisation, sales of vegan products have risen by over 30% since the introduction of the price parity.

Lidl GB is aiming for 25% of protein going through its tills to be plant-based by 2030. The latest figure is 18%, according to reports late last year, as the discounter called on the UK government to introduce plant-based targets as part of mandatory healthy food sales reporting.

What’s at steak?

There is a role for government here and the new memo outlines questions for policymakers, too. These include the assurances that will be in place to support the protein transition across the industry (as opposed to relying on individual firms to take competitive risks). The group also called on the UK government to explain how the national food strategy – on which more details are expected this year – address the continued, and expected increase, in reliance on cheap, intensively-produced meat and what incentives will be provided throughout the supply chain to encourage investment in ‘better’ meat and dairy and alternatives. And they also want to know what ‘peak’ livestock supply looks like in the UK given the environmental and health challenges ahead?

“We also need collective and coordinated action that cannot happen without the support of government,” the memo reads. The quality of conversations on the type, quality and quantity of meat and dairy consumed as a society, and the impacts of this, are “getting poorer”, it continues, and “[w]e are pushed towards binary stances”.

At its heart, this memo is about a loss of nuance. Food companies cannot be canned for chasing commercial opportunities. But boards are not being held accountable for the conflict this creates with their sustainability strategies – or the risks this brings in the short, medium and long-term. “There is a lot to be done within the rules of the game,” another of the insiders tells me, but there are also ‘rules’ that make it “impossible for even the most well-meaning CEO to do anything about this”.