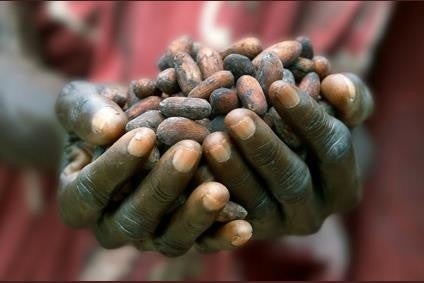

An open letter from two US Senators to the US Department of Homeland Security in July, calling for cocoa imports produced using child labour to be blocked and investigated by the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency, had a chilling and depressing resonance with the stand taken by Senator Tom Harkin and Rep. Eliot Engel almost two decades ago.

Nearly 20 years on from the signing of the Harkin-Engel Protocol by eight leading chocolate manufacturers, committing to rid cocoa supply chains of the worst forms of child labour, has so little changed?

In fact, a lot has changed but the time it has taken and the challenge still facing food companies looking to free their cocoa supply chains of child labour simply speaks to the scale and complexity of the issue.

The publication last week of Nestlé’s second progress report on its child labour programme offered some good news and genuine cause for optimism, while also providing a reality check.

The good news is Nestlé’s Child Labor Monitoring and Remediation System (CLMRS) has been scaled up and is continuing to deliver results. In the development phase from 2012 to 2017, the programme monitored some 40,728 children aged between five and 17 in Côte d’Ivoire cocoa-farming communities, identifying 7,002 children as being involved in child labour and bringing them into the remediation programme. Over the past two years, the programme has been expanded to include 78,580 children, with 18,283 child labourers identified and brought into the system.

Nestlé’s decision in 2012 to institute a CLMRS programme was significant in the context of industry-led efforts to tackle the child labour issue.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataWithout question, the structure of the cocoa supply chain in west Africa, as well as the poverty and lack of investment endemic in cocoa-farming communities, made the Harkin-Engel commitments highly ambitious and probably unrealistic. Food companies stressed these challenges continually when criticised for slow progress and missed deadlines but the lack of progress was not only a measure of the intractability of the issue but a clear indication that a change of approach was required.

For reputational reasons, food companies were extremely reluctant to make explicit admission of the presence of child labour in their supply chains, seeking to present it as a sector-wide problem. This had to change, and Nestlé was effectively the first company to put itself firmly – and individually – in the firing-line.

With Nestlé on a conference call last week to launch the report was Nick Weatherill, executive director of the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI), a multi-stakeholder organisation dedicated to advancing the elimination of child labour in cocoa, set up as part of the Harkin-Engel Protocol.

The core CLMRS concept was devised by ICI, and the organisation has worked with Nestlé and other food companies in devising and implementing numerous company-specific programmes since 2012. CLMRS aims to identify and remediate cases of child labour on a farm-by-farm basis, with facilitators working within cocoa-growing communities who raise awareness, identify cases and request remediation actions, which are then implemented by ICI in partnership with the chocolate company or cocoa supplier concerned.

Indeed, while Nestlé was keen to trumpet its progress, Weatherill had arguably even more encouraging news, reporting 12 companies are now operating some form of CLMRS programme, extending to 220,000 farmers, and covering around 15% of the supply chain in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

Whilst this is about food companies taking individual responsibility for the communities in their specific supply chains, ICI’s role offers an important collective element. The sharing of results by companies had been “instrumental in building scale”, Weatherill said, while the businesses’ tailored programmes were yielding “useful information about the nature of child labour and different ways you can address it and have impact”.

In terms of scale, covering 15% of such a fragmented and complex supply base with what is effectively a child-by-child intervention is a remarkable achievement. The reality check is 85% of the production is still not covered which, as Weatherill put it, “demonstrates how much more work there is to do: 15% to 100% in five years is going to take a huge amount of effort.”

However, the expansion of the programme is producing some economies of scale. According to ICI, the average cost of CLMRS has fallen from US$90 per farm to $70. Weatherill also detailed some refinements being explored, such as risk-based targeting and collaborating with other partners, notably the governments, “so that the burden of doing this is shared a bit more across the different actors that are out there”.

“There is a huge amount of work and investment required to tackle the root causes of child labour”

The progress since 2012, and the realisation a painstaking and nurturing approach to addressing child labour was required to address the issue, leaves food companies sourcing cocoa in a far better position than they might have been at a time when the public and regulatory focus on forced and child labour is sharpening.

In September, incoming European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called for “a zero-tolerance approach to child labour” in EU trade agreements. There has been mounting support for EU regulations requiring mandatory due diligence by companies with regard to both environmental and human rights issues in companies’ supply chains.

It is fair to say food companies buying cocoa from west Africa a decade ago would have been extremely exposed by such legislation. The CLMRS systems in place today provide a far more positive picture of a sector with a maturing understanding of the issue and its responsibility to address it. As Weatherill put it, CLMRS programmes are “helping companies meet growing burdens of expectation and obligation upon them”.

Indeed, confectionery companies Barry Callebaut, Mars Wrigley and Mondelez International joined with NGOs, including Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International, earlier this month setting out a shared position in support of strengthening due diligence requirements as they relate to cocoa supply chains. “An EU-wide approach to due diligence will benefit all actors in the supply chain in terms of a clear and consistent set of rules and common intent,” the joint proposition stated.

The letter sent by Senators Ron Wyden and Sherrod Brown to Kevin McAleenan, Acting Secretary of the US Department of Homeland Security, in July speaks to the increasing regulatory scrutiny, and followed an in-depth and troubling report in The Washington Post, examining the issue of child labour in cocoa. While that report underlines there is much to do and read like the exposés of 20 years ago, the situation is far more hopeful today.

Nevertheless, it must be borne in mind CLMRS is fundamentally about identifying where child labour is happening, bringing those children out of child labour and preventing them from having to go back into that work. There is a huge amount of work and investment required to tackle the root causes of child labour, chief among which is the grinding poverty of smallholder farmers in west Africa.

The expectations on food companies to invest further and return more value to these communities will only increase. Investing in, nurturing and supporting these communities to a degree that would not have been envisaged by food companies before the watershed of the Harkin-Engel Protocol is now the norm and the only sustainable way forward.