Mondelez International‘s decision to change the way it works with Fairtrade sparked questions about the future of the ethical certification. just-food contributing editor Ben Cooper argues Fairtrade still has a role to play for food companies looking to source more sustainably.

The interview Fairtrade Foundation CEO Michael Gidney gave just-food last week provides valuable insight on how the organisation sees the future of Fairtrade, the future of Fairtrade certification and, most crucially, the relationship between food companies and certification bodies.

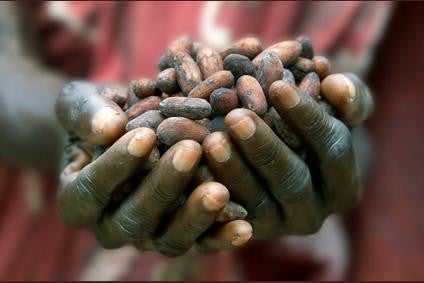

In particular, some contextualisation of the decision by Mondelez International to cease sourcing Fairtrade-certified cocoa for certain Cadbury products is instructive.

Does it signify big food is done with Fairtrade certification or with sustainability certification in general? Does it reflect that the relationship between food companies and sustainability certification is changing?

Gidney says Fairtrade is a change agent that must embrace change itself. While its relationship with Mondelez is evolving, what is being retained is the principle of third-party scrutiny that is a defining tenet of the Fairtrade movement.

Based on its original conversations with Cadbury, Fairtrade knew this day would come. The evolution is reflected in its own planning. A year ago, the Fairtrade Foundation published a five-year strategy, in which it states: “By 2020, we will have evolved from a single approach of certifying products to a portfolio of services.” At that time, the organisation was already piloting new projects and “value-add’ initiatives” with partners, expanding existing commercial relationships and creating new ones, “laying the groundwork for impact and revenue growth outside of traditional licensing”. That the new Mondelez deal and others that may follow is consistent with the organisation’s strategy appears incontestable.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataSo much for how Fairtrade views its evolving relationships with companies. What does the Mondelez decision say about how food companies view or may come to view Fairtrade?

Critically, while moving away from Fairtrade certification, the Cadbury owner sees a continuing role for Fairtrade, providing third-party scrutiny and credibility but also, as Gidney stresses, benefiting from the organisation’s considerable expertise and presence on the ground.

Mondelez’s decision suggests it believes Fairtrade can add value to its sustainable sourcing efforts. Looking at what Fairtrade has achieved over two decades, its footprint in so many origin countries and its global reputation, it seems extremely likely other food companies would come to the same view.

What form such partnerships may take remains to be seen. As this is a bespoke element of the Fairtrade Foundation’s work, the viability of partnerships will be defined by the capabilities of companies, the maturity of their sustainable sourcing strategies and the particular supply chains involved.

What will unify them, says Gidney, is the importance of prioritising farmer interests. Just as the terms of Fairtrade certification are exacting, meeting the terms Fairtrade is likely to lay down in future partnerships will not be easy for companies. However, the credibility Fairtrade’s endorsement and involvement will lend to sustainability programmes is not to be underestimated.

It would be quite wrong, however, to see Fairtrade as simply adding a reputational halo. It may be, as Gidney contends, the “best known and most trusted” ethical certification scheme in the world, but the work it has conducted in farming communities to build Fairtrade certification into what it is today gives the organisation enviable expertise and knowledge of the practicalities of development challenges, not least in how to engage farmers in solutions and work with governments and regional administrations in origin countries.

Gidney makes some important caveats regarding the potential for further partnerships with food companies. The regional concentration of cocoa production facilitates partnership with Mondelez’s own Cocoa Life programme, he says. It would be harder to set up comparable partnerships with programmes stretching across a more diffuse supply base.

He also alludes to the variability of company schemes, suggesting many still do not adequately focus on farmer engagement and raising farmer incomes, factors that would have to be satisfactorily addressed for a partnership to be considered. As time goes on, however, Fairtrade’s participation in partnerships should, in theory, make company programmes stronger in these areas. This would be welcome. As Gidney points out, company schemes tend to emphasise maintaining security of supply above all else, which he says also explains the greater focus on environmental rather than social issues. However, he stresses farmer poverty itself represents risk, rather than simply being an indicator of problems such as low yields or poor training.

What deals like that with Mondelez unquestionably bring is the opportunity for Fairtrade to act on a larger scale, to impact positively on the livelihoods of many more farmers than it can through certification alone.

That said, the engine by which Fairtrade built its international reputation, that still provides its unique selling point and sets it apart from most other NGOs and development organisations, is certification. Is that feature of the organisation’s work, which has defined it for the past two decades, under threat? Gidney says certification is “here to stay”, and the aspiration to continue to grow Fairtrade certification is in its five-year strategy too.

But, just as the adoption of Fairtrade and other sustainable certification schemes by major food companies like Cadbury, Nestle and Mars has offered substantial volume growth, opting to focus on their own programmes at the expense of certification could naturally have the opposite effect.

There are signs growth in Fairtrade-certified volumes in the UK is levelling off. The Fairtrade Foundation has just reported estimated retail sales in the UK for 2016 of GBP1.65bn (US$2bn), up just 2% from 2015. This time last year, the organisation also recorded a slight overall dip in retail sales, and a volume increase in cocoa for 2015 of 6%, versus the volume decline of 3% reported for 2016.

It should be noted growth in Fairtrade certification for many years had nothing to do with multinationals. It was in the hands of grassroots pioneer companies and niche brands. These can continue to be driving forces for Fairtrade certification. The food market is fragmented, niche players abound and there is always a steady stream of start-ups looking to take share from the mainstream. Strong ethical criteria are extremely important drivers in this area of the market. In the UK, the Fairtrade Foundation can also target growth in foodservice, and there are now 22 national Fairtrade organisations worldwide. Many of these are in an earlier stage of development than the Fairtrade Foundation.

However, looking towards the longer term, if more companies seek to take “ownership” of sustainable sourcing – a term Gidney himself is comfortable using – it follows Fairtrade certification in its specific and unique sense may become surplus to requirements for more companies, just as it has for Mondelez.

The balance, therefore, between certification and broader partnerships at Fairtrade in one sense depends on the progress food companies make with their own sustainable sourcing activities. Nevertheless, the pioneering work of Fairtrade has been a key catalyst for the improvements to date and is likely to continue to be, whether in the form of certification or broader partnerships.

Looking at sustainability certification more generally, as company schemes develop and improve, food companies may find they are increasingly meeting the sustainability criteria set by certification bodies. However, the degree to which companies will see a need or have the desire to focus consumer attention on their brands’ attainment of independent sustainability standards is an interesting question to ponder, particularly looking into the long term.

Ultimately, the ambition of many large companies may be for their names and their brands to stand for ethical values on their own without the ethical kite mark – on the back or the front of a pack – offered by Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance or any other certification body.

Brands evolved as a guarantee of attributes such as taste, product quality, food safety and provenance to the buying public. Food companies investing in improving standards in their agricultural supply chains and in sustainability generally want their brands also to signify the higher ethical standards they are seeking to implant.

Notwithstanding the investment and focus now being seen, the point where companies can realistically hope their brands will shine as true ethical beacons is still some way off. Moreover, Gidney suggests how ever advanced company schemes become they should never “mark their own homework”, making the analogy with financial reporting.

The comparison with financial accounting seems entirely reasonable. Public companies cannot operate without financial auditing, and it may well be desirable one day they should be legally bound to have their sustainability activities audited to the same standards of their financial accounts.

However, the more established the norms become, the less need there may be for overt signalling of sustainability credentials. After all, Unilever does not see the need to place the KPMG logo on every pack of Ben & Jerry’s.