A record-breaking drought across the Mediterranean has been adding to Europe’s ever-increasing food security woes, as parched Spanish soils inflict knock-on effects across the continent. In February and March, UK supermarkets reported a shortage of key salad staples, such as tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers. Meanwhile, olive oil prices are continuing to climb after Spain produced just 620,000 tonnes of olive oil during the 2022-23 harvest – down 58% on the previous year.

On 11 May, the then Socialist-led Spanish government approved an “unprecedented” €2.2bn ($2.36bn) plan to increase water availability via desalination plants and urban water reuse to help farmers maintain production. However, to many onlookers, this appeared to be no more than a sticking-plaster solution – and, to the more cynical, a measure aimed at the regional and local elections at the end of the month.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Indeed, two days after the announcement, SOS Rural – a national movement advocating for Spain’s agricultural sector – went ahead with a rally, taking to the streets of Madrid to protest against the government’s “ineffective, insufficient and untimely” drought policies.

Javier Santacruz, a Spanish economist and farmer, shared their pessimism, saying: “Partially tackling the economic consequences of drought without first making the necessary reforms to integrate food markets and without putting in place the necessary water infrastructure, stocks and distribution will most likely lead to an unsatisfactory outcome.”

Spain’s water wars are political

Unfortunately for the long-termists, water governance has become a major political hobby horse amongst Spain’s sparring leaders – and never more so than in the build-up to the country’s regional elections in May and its general election in July.

The socialist-led government, however, curried little favour with producers and farmers in April, when they took the EU-endorsed decision to increase the Tagus river’s water levels by decreasing the diversion of water into the Segura – a vital lifeline to the alluvial crop-growing plains in the south east of the country.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataIn the same month, the Andalusian government, led by the right-wing Partido Popular and far-right Vox, seized on farmers’ discontent, approving a controversial bill to increase irrigation near the drought-stricken Doñana National Park. If passed into law, it will regularise the activities of farms that already use illegal wells to grow strawberries for export across Europe.

While gaining local producers’ support, ecologists, opposition parties and European legislators fear that Andalusia’s plan will further dry out Doñana, threatening a vital wetland that is critical to the region’s water security as well as its multi-billion euro legal strawberry industry.

Andreas Baumüller, Head of Natural Resources at WWF’s European Policy Office, believes that the law will breach EU rules: “The European Commission must not stand idly by while the Andalusian government is on the brink of flagrantly breaking both the EU Water Framework Directive and the EU Habitats Directive – again. The Commission must continue demanding compliance with the European Court of Justice ruling, including closure of all illegal farms and increased efforts to conserve Doñana.”

Regardless of the proposal’s legal viability, the ESG heat is building for European importers of Andalusian “drought berries”. In July, Germany, which imports 30% of its strawberries from the province of Huelva, sent a delegation to investigate the proposal’s ecological consequences and meet with their Spanish counterparts, while the consumer group Campact, having now harvested some 270,000 signatures, continues to petition the likes of Edeka and Lidl to stop selling fruits grown with “looted water”.

Spain’s hotter and more arid future

Spain’s water problem isn’t new, nor is it likely to disappear anytime soon: in 2019, the Spanish association La Unión de Uniones de Agricultores y Ganaderos (the Union of Farmers and Ranchers) reported drought-related losses of €1.5bn, while research by TU Graz University of Technology found that the European continent has been suffering from a severe drought since 2018 with chronically low groundwater levels.

Earlier this year, COAG, Spain’s principal farmers association, warned that recent droughts had already inflicted “irreversible losses” on over 3.5m hectares of rain-fed wheat and barley. Water restrictions for irrigation, they said, were also threatening the viability of fruit trees in Andalusia, Murcia, Valencia and Catalonia, and in the southern part of Andalusia, olive trees and rainfed nuts would barely exceed 20 percent of a normal harvest. Crops, they said, will be affected, not only by present droughts, but also by the deficit carried over from the previous season.

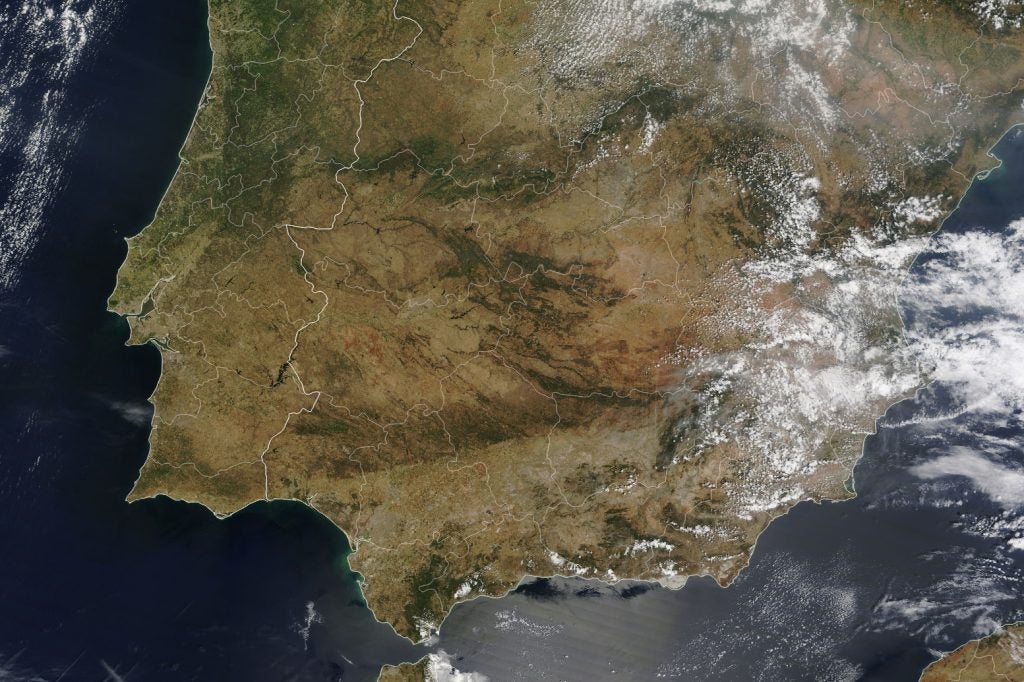

However, while Spanish producers unite in their calls for an end to irrigation restrictions, environmentalists say that the curbs are simply preparation for the effects of anthropogenic climate change. In July, Greenpeace issued its latest warning: Spain, with a climate said to warm by 1.5℃ for every degree of global warming, is headed for a hotter and more arid future. Images collected by NASA’s Terra satellite (below) illustrate where already parched green vegetation in May 2022 (top) turned brown by May 2023 (bottom), having received 28% less rain than expected in the current hydrological year.

What, then, lies ahead for Spain’s embattled agricultural sector? Cindy van Rijswick, global strategist for fresh produce and farm inputs at Rabobank, tells Just Food the coming autumn and winter will be particularly challenging for food processors sourcing tomatoes, potatoes and onions, in terms of both availability and raw material prices.

Over the longer term, she says, “extreme weather events will become the new normal, and companies need to be prepared for that. They may wish to diversity their sourcing regions and companies, co-invest in measures to deal with this on-farm (e.g., better irrigation systems, precision farming), or simply become a very loyal long-term partner for growers, so in case supply is lower they are the first to get the produce”.

Guy Singh-Watson, the founder of Riverford, the direct-to-consumer veg box delivery company, recently expressed the challenges facing its sourcing strategies in Spain: “Everywhere, competition for ever-scarcer water is a growing issue. We recruited growers further north but Catalonia is now one of the worst affected areas, with restrictions on irrigation that are drastically affecting quality and yield. In Murcia, 40% of water now comes from the sea – but with an energy cost of 3 kwh per cubic metre and issues around marine water intakes and brine discharge, desalination can come with its own environmental costs.”

Now, the company is pursuing a strategy of infrastructure investment, building reservoirs and increasing water capacity, as well as crop diversification, with a move towards deeper-rooting perennial crops, Singh-Watson says: “[O]ne of our oldest and best growers near Granada is slowly transitioning from garlic, asparagus, and spinach, to deep-rooting drought-resistant olives. Some crops will need to move north; others will need to be grown under the protection of polytunnels and glass, reducing water usage and giving better control of weather risks.”

Adoption of agri-tech must accelerate

At the EU AgriResearch Conference in May, Luis Planas, Spain’s then Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, invoked the pressing need for new technologies in the agri-food sector, calling for increased synergy between scientific advances and their application to the real needs of agriculture and business.

Spain is a leader in the European Innovation Partnerships (EIP-Agri) scheme, having already financed 124 innovative projects and 177 operational groups to the tune of €70.8m. Now, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food has increased the budget for the new period 2023-2027 to €75m.

Recent projects that have been funded in Spain under the scheme include an operational group working on “new irrigation systems from oval pipes with low flow emitters”, designed for better water management, and an operational group working on “a network of sensors that collect the meteorological and soil data required to determine the water availability in vineyards” in order to adapt vine cultivation to climate change. Another project combined “innovative irrigation reduction strategies” with the use of mycorrhizal-forming fungi, which improves plant performance under drought.

Rates of global agri-tech adoption, however, leave a lot to be desired: a recent survey by McKinsey found that just 5% of farmers worldwide are using sustainability-related technology, such as software and hardware that measures and optimises irrigation systems. More worryingly, the increase in the adoption of agri-tech looks set to be limited over the next two years, with just 4% of farmers saying they plan to either adopt either farm-management software, precision-agriculture hardware, remote-sensing solutions, or sustainability-related technologies. The biggest barriers to adoption appear to be high costs, unclear ROI, and complexities in setup and use.

Van Rijswick says growers cannot bear the costs of climate change alone, and that, alongside government aid, downstream supply chain partners should expect to invest in their partners on the ground (either by directly investing capital in farms or by paying higher prices for produce).

Governments will also need to dig deep, she says: “Agriculture and horticulture are of high strategic importance for the region, not only because of high export earnings but also for the survival of rural communities.” There may be some signs of optimism in this department: Partido Popular leader Alberto Nunez Feijoo said a Spanish government led by his party would invest €44bn over six years in water infrastructure.

However, Spain’s transition to a less water-intensive and more drought-resistant agriculture will be a long and hard-fought battle, requiring cooperation, diversification and innovation across the value chain. At Riverford, Singh-Watson offers some wise words: “Rather than assuming that we can buy our way to food security in an increasingly fragile global market, we need to plan and invest in the infrastructure that will, at least, reduce the disruption ahead.”

This article initially appeared in the September 2023 issue of Just Food’s digital magazine